The Answers to Questions on Scaling Agentic AI are Already in History

The past may or may not be prologue, but during seismic technology transitions, history is often instructive.

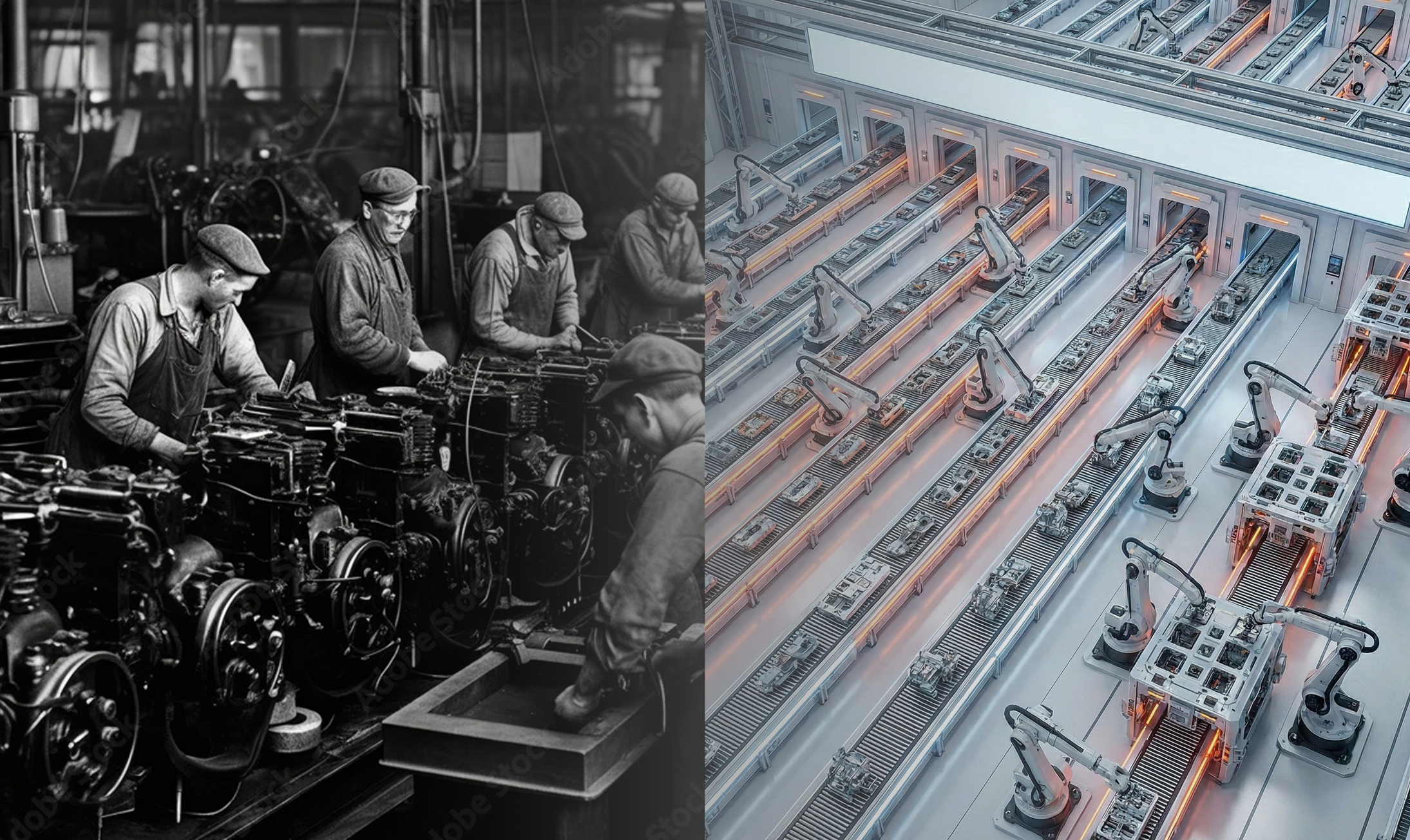

In the early 20th century, Rolls-Royce and Ford Motor Company represented two radically different answers to the same question: how should complex technology be built, sold, and scaled? Between 1907 and 1926, Rolls-Royce produced roughly 7,900 Silver Ghost automobiles. Each was meticulously engineered and assembled, relying heavily on skilled craftsmen and limited standardization. These vehicles were prized by industrialists, financiers, heads of state, and other high-net-worth buyers who valued performance, craftsmanship, and exclusivity over price or interchangeability.

At roughly the same time, Henry Ford pursued a fundamentally different path. With the introduction of the moving assembly line in 1913, Ford transformed automobile manufacturing into a highly standardized, repeatable process. Over its production run, more than 15 million Model Ts were built. Prices fell dramatically from ~$850 at launch to under $300 by the mid-1920s. This affordability brought car ownership within reach of the mass market.

The Model T was not a luxury product. By modern standards, it required frequent attention and maintenance. Oil had to be changed for the Model T every 50-100 miles. But it was designed around interchangeable parts, simplicity, and repairability. Thousands of standardized components could be sourced, replaced, modified, or extended. That design choice catalyzed something far more powerful than Ford alone could have built: a broad and durable aftermarket ecosystem of mechanics, parts suppliers, converters, and innovators. Farmers adapted Model Ts into tractors and snowplows, while entrepreneurs built businesses servicing and extending the product’s lifecycle. A large, growing population now had a vested interest in the Model T’s continued success.

Rolls-Royce, by contrast, built a smaller but extraordinarily valuable franchise at the high end of the market. Its engineering excellence endured, eventually expanding beyond automobiles into aircraft engines – where Rolls-Royce remains one of a small number of global leaders today. In fundamentally different ways, both companies succeeded in serving customers with different economics, ecosystems, and scaling dynamics.

What Does This Have to Do with Agentic AI?

Agentic AI today resembles the early automotive era more than most care to admit. Much of what is labeled “Agentic AI” remains bespoke. Systems are assembled manually, tuned through expert intervention, and behave probabilistically by design. The inherent variability is simultaneously a feature and a liability: it enables flexibility and adaptation, but complicates reliability, budgeting, governance, and trust. In this environment, it is tempting to focus on technical superiority in model performance, autonomy benchmarks, or novelty of agent behavior. History suggests that this focus alone is insufficient. Widespread adoption will hinge less on who builds the most sophisticated agents, and more on who standardizes the production of agentic outcomes to scale Agentic AI.

That implies several things:

- Repeatable agent pipelines rather than one-off deployments

- Lifecycle management tooling to plan, test, validate, observe, and maintain agent behavior over time

- Stable APIs and interfaces that allow partners, consultants, and integrators to build reliably on top of core platforms

- Predictable pricing and packaging that enterprises can budget for, govern, and scale

- Consistent outcomes that reduce operational risk and enable institutional trust

Standardization does not eliminate innovation – it enables ecosystems. Just as interchangeable parts created a thriving Model T aftermarket, standardized agent frameworks and interfaces will allow third parties to extend, specialize, and commercialize Agentic AI in ways no single vendor can anticipate.

The long-term winners in Agentic AI are unlike...